- Home

- Bret Boone

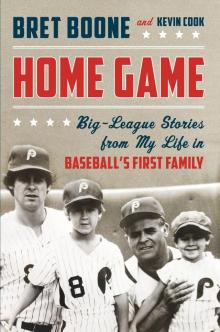

Home Game Page 4

Home Game Read online

Page 4

I can’t explain why stuff came so easy and early to me. It’s not like I was the world’s greatest athlete. Later in life I’d run into guys who really were great, once-in-a-generation talents, and believe me, I know the difference.

Maybe it’s just that I was so eager to get on to the next thing, to get on with life. Patience was never my strong suit.

My folks never said I was great or amazing. They wouldn’t want me to get a big head. But there was one word they did use to describe little Bret. Gramps, Grandma Patsy, Mom and Dad, my aunt Terry and the rest, they used the same word. Fearless.

At least it sounds better than freakish.

You couldn’t script my life any better if you tried.

My first memories are of mornings at my grandparents’ house. Waking Gramps up at dawn. That’s when we began our tradition of playing ball in his yard. It must have started in 1970, because Dad was serving in the Army Reserves. It was the middle of the Vietnam War. Mom and I went to stay with Gramps and Grandma Patsy in San Diego. I’d toddle into the master bedroom every morning about six, poke him in the foot or the belly, and go into my usual routine: “Ball, ball!”

Gramps dragged himself out of bed, but he wouldn’t play with me right away. First he brewed a pot of coffee, the one thing he couldn’t do without. Coffee and the sports page. He lifted me onto his lap while he paged through the baseball stories and box scores in the San Diego Union. And then, finally, we’d go out to his yard to have a catch.

I didn’t know it then, but we were only a couple of miles from the fields where Gramps played when he was a kid, following Ted Williams from the local sandlots to the slightly better field at Hoover High School. Now, almost forty years later, he was stretching his achy legs, underhanding Wiffle balls to his year-old grandson while the sun came up.

Gramps wasn’t sentimental about his playing days, but he kept a few old bats around the house. Not in a trophy case or anything. They were just old, tar-stained bats from the 1950s lying around. I liked to feel the grain in the wood. Those dinged-up Louisville Sluggers were as tall as me, and twenty years older. I couldn’t swing them yet. I couldn’t even pick them up, but something about the feel of the grain stuck with me, like the dry leather of an old glove or the calluses on Gramps’s hand. Years later, when other big leaguers started switching to maple bats, I stuck with Louisville Sluggers made from white ash. If old-fashioned wood was good enough for Gramps and Dad, it was good enough for me.

After Dad got back from the army and made it to the big leagues, he played winter ball in Puerto Rico. That’s where I knocked tennis balls around with his friend Frank Robinson, the Hall of Fame outfielder who was one of the seven or eight best hitters ever. To me Frank was just the nice man bunting a ball over the net to me. And to him I was Bob Boone’s little loose cannon, rearing back and smashing the ball at him as hard as I could.

Frank never saw me plunging into a pool near the tennis courts, but it seemed like everybody else in Puerto Rico did. I was climbing the ladder to the high dive when the poolside crowd started noticing. They’d never seen a two-year-old climb up there. Some of them ran to my parents. “We’ve got to save him!”

Dad shook them off. “Just watch,” he said. The other adults stood around the pool looking worried, pointing at the toddler on the high dive. Finally I toddled to the end of the diving board and leaped off. Everyone was flipping out—till I splashed to the surface, waving to the crowd.

After that, Mom sat in a beach chair by the high dive. When people got scared for me she told them, “It’s okay. He’s just precocious.”

Life was fun, and the best thing of all—hitting a ball with a bat—was easy. We lived in Medford, New Jersey, across the bridge from Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. My parents settled there during Dad’s rookie year with the Phillies. I played T-ball in the local Little League, but let’s get one thing out of the way. My dad didn’t teach me to play. Fans picture big-league dads on the Little League field with their sons, showing them how to grip and swing a bat. But ask yourself—when would that happen? My Little League games were on weekend afternoons. Dad was either catching at the Vet, a twenty-minute drive away, or on a road trip. Gramps had more to do with my early days of swinging plastic bats at Wiffle balls, but except for the year Mom and I spent in San Diego, he lived three thousand miles away. I saw Gramps mainly on Thanksgiving and Christmas.

So who taught me?

That’s a question every second-generation player has to answer. It’s a sore point to some. Barry Bonds wanted his dad to come to his Little League games, but Bobby Bonds—a three-time All-Star who hit 332 home runs—was busy playing for the Giants and seven other teams. The McRaes were like that, too. Hal McRae, a 1970s star, never saw his son Brian play a single ballgame until Brian was a pro. Same for my Seattle teammate David Bell and his father, Buddy, a great third baseman of the 1970s and ’80s. David and his brother Mike idolized their dad when they were young, but it’s not like Buddy was in the backyard, having a catch with them. He was playing for the Indians, Rangers, and Reds.

I was talking with Dad about this. He said, “Your grandfather was right. You were a born hitter, that’s all.” And while Dad never showed me how to swing a bat, he taught by example every day of the week. One day when I was five or six, he was in our backyard, building a swing set for Aaron and me, when his back locked up. He yelled like he’d been shot. The Phillies had a game that night, so our neighbor Greg “the Bull” Luzinski, the Phils’ homer-hitting left fielder, picked him up and helped him to the car. Greg drove them to the stadium, where the trainers shot Dad up with painkillers. Then he went out and played. For the rest of the season, Dad’s back would seize up in the late innings. He’d twist and stretch and stay in the game.

He played with a broken finger on his throwing hand and torn cartilage in his knee. He played the 1980 World Series on a broken foot, and never complained. Aaron and I saw all that. Even if nobody ever said a word about it, we saw what it meant to be a gamer. While my father might not have been around to teach me how to grip a bat, he taught me how to be a pro and how to be a man.

But I’m my own ballplayer, always was.

In those days, we had a tri-level house in a woodsy part of Medford, at the end of a cul-de-sac called Sunrise Court. There was a basketball hoop, a pool in the backyard, three cars in the driveway. One of the cars was a black El Dorado, a free lease to Dad from a Phillies-fan Cadillac dealer. Then there was Dad’s Datsun 280Z, also black, the sports car he loved to drive fast. He and Luzinski drove to work together, zipping across the Walt Whitman Bridge from New Jersey to Philly, waving to fans who waved and honked their horns. Dad might have gotten a lot more speeding tickets if most of the cops hadn’t been Phillies fans, too.

Mom’s station wagon got the most mileage. She’d drive us kids to school and the mall and about a hundred ballgames a month, especially after Aaron joined the home team in 1973. Dad had promised my mom he’d never miss the birth of any Boone of his after he missed mine, but Aaron came along when Dad was on the road. There was no paternity leave in those days. He didn’t lay eyes on Aaron until Mom took us to meet the Phillies on the road six weeks later. At that point, in 1973, Dad was 0 for 2 in terms of seeing his sons enter the world.

But he was moving up in the world, making $100,000 by the time I got to grade school. That’s worth about half a million today. Before long he’d be up to $400,000, thanks to Marvin Miller and the players’ union. So we were comfortable, but not snooty about it—Bob and Sue Boone never put on airs. They never let Aaron and me think we were anything but regular American kids. It might seem a little weird when we’d make a family trip to the grocery store and other shoppers asked Dad for his autograph, but he said that was nothing special. “They see me on TV, that’s all.” The only autograph seeker who annoyed him was a fan who asked me to sign a baseball. I was still a Little Leaguer, but the guy must have thought I had a big-league future. Dad stepped between us and told him, “Leave

my boy alone. Just let him be a kid.” Other than that, he said signing autographs was just part of the game, and he felt lucky people cared so much about baseball that he could play it for a living.

That was Dad all over, Mr. Good Citizen. Aaron was like that, too, the Boones’ little angel, but I had some mischief in me. Okay, maybe a lot. Nothing nasty or malicious, but if a kid was building a ramp to fly his bike over trash cans in the driveway, Evel Knievel–style, it was probably me. If a mouse turned up in the laundry, or the dog was on the roof or the mailbox caught on fire, I was the prime suspect. Dad had the idea that he was the disciplinarian in the house, the sheriff of Sunrise Court, but it never quite worked out that way. He was busy catching 140 games a year for the Phillies. That left Mom in charge of the Boone boys, and I was faster than she was.

If I was in for a spanking, I’d take off running around the yard. She’d chase me till she got winded and gave up. “Just wait,” she’d say. “Wait till your father gets home!” But by then it would be late at night. Dad would have caught nine innings, talked to reporters, showered and dressed and made the drive home, and we’d all be so happy to see him that I got off scot-free.

Our house was like a theme park for Aaron and me and our friends. We had the swimming pool, plus a tree house and a zipline between oak trees, one of the first backyard ziplines in New Jersey. After school, we played pickup games. Every sport in its season, plus a lot of street hockey; it’s the national pastime of suburban New Jersey. Kids strap on roller skates, set up a couple of goals, and pretend they’re the Broad Street Bullies of 1975. This wasn’t the neighborhood moms’ favorite game, due to the traffic on Sunrise Court. But we had it under control. When a driver came around the bend we’d yell “Car!!” and hustle up the driveway. After the car went by and the coast was clear, we’d get back to the game. It was the kind of spontaneous, unsupervised fun today’s overscheduled kids never seem to have. We’d just get a bunch of kids together and play, with no adults keeping stats, nobody taking pictures, nothing to gain except fun.

Our three-car garage was full of footballs, basketballs, and soccer balls, as well as bats and baseballs Dad brought home from the Vet. With buckets of baseballs in the Boones’ garage, no kid on our street ever had to pay for one. We had bikes, a moped, and a couple of snowmobiles. In the winter we’d snowmobile around the neighborhood, dodging trees. Then we’d pile into the basement and put on a show.

That basement was Dad’s favorite room. There were a couple of couches and a pool table down there. Framed pictures of his teammates and friends—Schmidt, Luzinski, Tom Seaver, Carlton Fisk—lined the walls. There was a bar where Dad could serve friends and teammates the latest cabernet recommended by Philadelphia wine connoisseur Steve Carlton. There was a trophy case for Dad’s plaques and trophies, like the Gold Glove he won in 1978, his first of seven. Over the years Aaron and I would add trophies of our own to that display case, but when we were little we contributed mainly noise. We’d get tired of watching Happy Days or Laverne & Shirley and chase each other around the couches, jumping over the dog, Wegian, a nervous Norwegian elkhound. Then we’d climb onto the carpeted platform at one end of the room. Aaron and I and the neighborhood boys used that platform as a stage to entertain the grown-ups. We’d act out the latest Wrestlemania, with me as Hulk Hogan, in front of a wall covered with giant paintings of Bob Boone.

Paintings? Oh yeah, Mom hired a local artist to cover the wall with life-size pictures of Dad catching and hitting. To me, that basement wall seemed as normal as the picture window upstairs. Same for the buckets of baseballs in the garage, the mitts with Dad’s name stamped in the leather, the Bob Boone–model bats, and the big, muscly teammates who were his friends—none of that struck me as anything special. I mean, didn’t everybody have Pete Rose and Greg Luzinski drop by after work, and action paintings of their dad on the wall?

The Boones and Luzinskis were tight. Dad and Greg met as teammates in the low minors in 1969, the year I was born. Dad and Mom were twenty-one years old, living in a little apartment in Durham, North Carolina. The Bull was eighteen, a year out of high school, already six one and about 225, when he pulled my mom aside and said, “Sue, my girlfriend’s coming to town. What do I do? Can you help me out?” Mom must have been a good helper. She showed Greg’s girlfriend around Durham, and Sue Boone and Jean Luzinski have been friends ever since.

“We went through the minors like baseball wives do,” Mom says. “It was guys on the road and girls together, helping each other. Cooking together, doing laundry, babysitting—all the glamorous stuff.”

Ten years later we lived up the street from the Luzinskis in Medford, on opposite sides of a little lake. I’d hop on my bike and ride over to the Bull’s house. Greg and Jean’s daughter Kim was my age. Their son Ryan was Aaron’s age.

Ryan and Aaron looked up to me, of course, and why not? I was a Little League stud, four years older, while they were topping grounders in T-ball. What I remember about Aaron and me at that age is trying to be a decent big brother to him. I let him tag along and play ballgames with me and my friends, so he grew up competing with older boys, getting better fast. And not just at baseball. In those days, kids weren’t so specialized. We played baseball all summer, football in the fall, and basketball in the winter.

I think specialization is a key factor in today’s sports, and it’s a double-edged sword. Today’s kids tend to pick one sport—sometimes even one position—and play nothing else from an early age. They’re exclusively pitchers or quarterbacks or strikers or point guards long before they hit puberty. They get better training than ever before, and by the time they get to high school, some of them are as polished as I was in college. By the time they make the pros, they’re the best-trained, hardest-throwing, hardest-hitting generation in sports history. That’s one reason the talent level keeps going up. Today’s average player is better than the average when I came up in 1992. In fact, today’s average player is probably better than the All-Stars of Gramps’s day.

But do today’s players have as much fun as my grandpa, my dad, my brother, and I had? Do they love the game as much? Do they enjoy it? I’m not so sure about that. Sure, talent matters. Technique matters. Strength, speed, and high-tech training all have their place. But fun should matter, too.

Here’s a related worry—baseball’s injury epidemic. Specifically pitchers. Everybody wonders why so many pitchers keep hurting their arms. Back when Dad was playing, only one player in the majors had “Tommy John surgery” to reconstruct his elbow: the Dodgers’ Tommy John. Today the number is five hundred and climbing fast. A record thirty-one pitchers had the operation in 2014. Some never made it back to the majors. Others came back better than ever, with an extra tick or two on their fastballs. My dad, who runs the Washington Nationals’ minor-league system, says the Nationals plan to give all their kid pitchers Tommy John surgery, “just to get it over with.” He’s joking, but you get the point.

I keep thinking that a lot of those pitchers with blown-out arms might have been better off trying lots of sports, the way kids did when childhood was less of a job. Instead, many if not most kids now play on Little League teams, school teams, and travel teams from the time they’re in first or second grade. Picture the strain on all those young, growing arms. They just throw baseballs as hard as they can, over and over and over, until they learn to twist those muscles and tendons to make the ball curve, and then they repeat that motion thousands more times.

Does that sound like fun? Or stress? Kids should have a chance to be kids—and to figure out what their favorite sports are, without specializing at such a young age.

Of course, for Aaron and me, baseball season was the best—especially when the Phillies had a home stand. I’d come home from grade school with a full head of steam. “Dad, c’mon, let’s go!” We’d pile into his car—Dad, Greg Luzinski, Greg’s son Ryan, Aaron, and me—for the twenty-minute drive to the ballpark, with us antsy kids climbing all over our dads.

P

hillies manager Danny Ozark was like the world’s coolest uncle. A round-faced, grizzled old baseball lifer with a quick smile, he was friendly and funny. It was Ozark who once claimed, “Ninety percent of this game is half mental,” a line most people think Yogi Berra said. And thanks to him, the Phillies had the family-friendliest clubhouse in the league. (Note to readers who didn’t grow up in a ballpark: a baseball clubhouse is the locker room. It just sounds friendlier.) Aaron and I had our own locker and mini-uniforms. We’d bomb around the clubhouse on our Big Wheels—plastic tricycles that were a popular toy in those days—rolling over Ace bandages, jerseys, and jockstraps. We took grounders on the field before the game, and shagged flies in the outfield while Dad, Schmitty, and the Bull took batting practice. Once the game started we’d explore the stadium, a couple of grade school kids in pint-size Phillies uniforms playing tapeball in the equipment room. Swinging yellow Wiffle bats, we’d knock a rolled-up ball of duct tape off a wall—that was a single—or a roll of tarp for a double, or off a John Deere tractor for a homer. Later on we’d join Mom to see if the good guys won the game.

In the middle of July 1979, Mom was nine months pregnant with her third child. Her due date happened to be the same week Dad was selected as the National League’s starting catcher in the All-Star Game at the Kingdome in Seattle. He couldn’t miss that. Who knew if he’d ever start another All-Star Game? Dad swore he’d play the game and fly straight home the next day, probably in time to catch the baby. So she told him to go to Seattle. “And take Bret and Aaron with you.” She didn’t need me doing dirt-bike tricks in the driveway when she went into labor, which is why I wound up on national TV at age ten.

The All-Stars were the main attraction. Steve Carlton and Dad were the National League’s starting battery, going up against Nolan Ryan and an American League lineup featuring George Brett, Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Rice, and Fred Lynn. But some of the biggest cheers came an hour before the game, when the stars took batting practice. In those days before fears of legal liability ruined all the fun—what if a child got hurt?—players’ kids got to field the balls that stayed in the park. You can probably guess which kid made the most of his moment on the field. I ran to the outfield, a four-foot-tall third grader with a glove that was about ten sizes too big for my hand, and started snagging long drives on the warning track. Pretty soon, fifty-eight thousand fans were watching the little squirt in the Phillies uniform, not just Yaz and Brett, while I milked my first All-Star moment for all it was worth. Pretty soon I was showboating, turning my back to the plate and catching fly balls behind my back. Just showin’ off.

Home Game

Home Game